2022 Award Winners

M-0. Elementary 3rd and 4th graders (immersion, FLES or any program)

すなのしろ なみとワルツの かもめかな

ヘイモンド・ブレイディー Brady Haymond, Fox Mill Elementary

天 This is a very creative poem that exemplifies the technique of personification (gijinka 擬人化) and suggests a double entendre in the first line between “castle” 城 and “white” 白, which is the color of the かもめ. The use of the emphatic final particle かな is perfect here, and we can easily imagine your discovery at the seagull hopping back and forth on the beach as if dancing with the waves!

さくらんぼ ゆきにかくれて あかくなる

伊藤友那 Yuna Ito, Fox Mill Elementary

地 Lovely imagery that calls to mind a very traditional color scheme of red and white. In classical times, the practice of kasane 襲 involved the layering of clothes of different colors. There were many color schemes, and even today “kasane colors” (kasane no irome 襲の色目) are a topic of interest for many. One wintertime combination was called yuki no shita (雪下) and used the color white on top of the color crimson (kurenai 紅), which is of course a reddish color close to aka 赤. Altogether, your verse is perfect for winter!

せきらんうん もくもくあばれ かいじゅうだ アジー・ジャック Jack Agee, Fox Mill Elementary

人 This is a creative poem that begins with a hypermetric (ji-amari 字余り) line and uses two Sinitic (kango 漢語) vocabulary words of a sort not usually seen in poetry. The cumulonimbus clouds “rage in silence” and are implicitly likened to a giant kaijū 怪獣, transforming them from an insentient phenomenon of Nature into an active, living entity. Bravo!

Haiku is a wonderfully capacious literary form, and the bold use of a specialized scientific term (積乱雲) shapes the aesthetic experience of this verse.

M-1. Elementary 5th and 6th graders (immersion, FLES or any program)

ゆきがふる そとであそぶよ こどもたち

ジェイミー・シャイド Jamie Scheid, Great Falls Elementary School

天 Nice verse capturing the playful innocence of childhood in wintertime. Haiku are suitable for both profound philosophical insight and the lighthearted joys of everyday life. Indeed, the form often aspires to the erasure or collapse of such distinctions, achieving in the best cases a unity between the profound and the quotidian. This sort of duality has a long history in Japanese poetry, and is broadly reflected in the distinction between the more philosophical, “serious” (ushin 有心) orientation and a more “non-serious” (mushin 無心) orientation in linked verse (renga 連歌), or in the longstanding distinction between the “refined” (ga 雅) and the “vulgar” (zoku 俗).

さくらさく ももいろのえだ はながまう

ウィリアム・キリアン William Killian, Great Falls Elementary School

地 Pink! The color scheme in this verse is very nice, and the implicit personification in the final ku is very well done. The image of blossoms “dancing” in the wind surely touches what traditional Japanese poets would have called the “fundamental significance” (hon’i 本意) of springtime.

つゆおわり にじがかかって なつがくる

さな・ロドリゲズ Sana Rodriguez, Great Falls Elementary School

人 A solid poem using pleasant imagery to herald the coming of summer. Each ku contains one central image, and the progression from one ku to the next tracks the temporal progress of the three images: つゆ → にじ → なつ. All in all, a very well-structured verse.

M-2. Middle school 7th and 8th graders (immersion or any program)

春か冬? 花があるけど どこも雪

ビアンカ・ルーナ・アンテロ Bianca Luna Antelo, Lake Braddock Secondary School

天 This poem exemplifies a very traditional conception. In premodern Japan, spring in the lunar calendar (inreki 陰暦) generally begins around mid-February, which means that “spring snow” (shunsetsu 春雪) is an extremely common phenomenon and appears frequently in classical Japanese poetry. Of course, the reader based in America assumes that you’re talking about scenes close to home,

but the imagery tracks well either way, since Japan’s climate is roughly similar to that of much of the U.S. Eastern Seaboard.

Moreover, beginning the poem with a question is an intriguing move, one that recalls two separate classical poems. The great ninth-century poet Ariwara no Narihira 在原業平 (825-880) seems to have been fond of this move, as two of his most famous poems begin with questions:

Kimi ya koshi? 君や来し Did you come to me? Ware ya yukiken? 我や行きけん Or might I have gone to you? Tsuki ya aranu 月やあらぬ Is this not the moon? Haru ya mukashi no 春や昔の Is the springtime not Haru naranu 春ならぬ That springtime of old?

And the very first verse in the classic waka 和歌 anthology Kokinshū 古今集 (905) treats a theme similar to that of your verse:

Toshi no uchi ni としのうちに Within the (old) year, Haru wa kinikeri 春は来にけり Springtime has come. Hitotose o 一年を Shall we therefore call Kozo to ya iwan こぞとやいはん The current year “last” year? Kotoshi to ya iwan 今年とやいはん Or shall we call it “this” year?

Such is the power of poetry; your verse proliferates connections in the minds of readers even when such connections may not have been intended. This is at the heart of an important phenomenon in literature known as intertextuality (kan tekisuto sei 間テキスト性).

あきのかぜ こうようおちる うつくしき

マイルズ・グロセット Miles Grossett, Hayfield Secondary School

地 I notice you chose to end the final ku in the classical rentaikei (連体形) — a perfectly sensible choice given that the classical shūshikei (終止形), うつくし,

only has four syllables! The rentaikei has several uses, the most common of which is to modify nouns (e.g., うつくしき花). It can also be used to end sentences, as you have done here, and this is especially common when certain medial particles known as “bound particles” (kakari joshi 係助詞) are present.

We could even rephrase your verse slightly to admit of more classical grammar: you have used the modern verb おちる, but in classical Japanese this verb is おつ and its rentaikei is おつる. Hence, using the particle ぞ in a so-called “bound structure” (kakari-musubi 係り結び), we might see something like the following: あきかぜに、おつるもみじぞ、うつくしき. Here, おつる modifies もみじ (a synonym for こうよう), while the ぞ invites us to end the sentence in the rentaikei うつくしき. Bungo 文語 grammar is lots of fun!

J-1. High school Japanese 1 equivalent (may include 8th graders)

はなおわり もどるやくそく はるをまつ

ロミシャ・ランジッチャー Romisha Ranjitkar, Oakton High School

天 The idea behind this verse is lovely: the blossoms, archetype of both evanescence and cyclicality, will be back next year. Is it the blossoms who promise to return, or is it you who promise to return to them? The flow of the poem suggests the former, but the ambiguity is productive and makes for an enjoyable verse.

たんぽぽは きれいな空に 飛んで行く

エンマ・シュミジゲン Emma Schmiedigen, Walt Whitman High School

地 This is a good example of a streamlined, declarative verse that uses simple, prosaic language to describe a lovely scene. It is a sentence — exactly as it would

appear in prose writing (i.e., without perturbation of word order (tenchihō 転置法) or other rhetorical techniques (hyōgen gikō 表現技巧)) — but it accomplishes its aim splendidly. The dandelion is also a perfect haiku flower: both lovely and ordinary, it is well suited to a medium like haiku, which as I noted above has been honed to treat the simple joys of everyday life.

なつのすな たいようのした リラックス

アッシュリー・チャールズ Ashley Charles, Paint Branch High School

人 A day at the beach! In each of its three ku, this verse uses traditional Japonic vocabulary (wago 和語), Sinitic vocabulary (kango 漢語), and English vocabulary. Unlike classical waka 和歌, haiku have essentially no constraints on diction: you can use whatever vocabulary you want; this makes the form perfect for treating everyday life.

J-2. High school Japanese 2 equivalent

揺れる花 春色の滝 花吹雪

カミラ・ウェルボーン Kamilla Welborn, Lake Braddock Secondary School

天 Very good diction here in the use of 滝 and 雪, each of which figure a different aspect of blossoms being blown about in the wind. The association of cherry blossoms and snow is ancient, and 花吹雪 is one of several words in which that association is foregrounded. Another is the expression sora ni shirarenu yuki 空に知られぬ雪, literally “snow unknown to the sky,” which also means “cherry blossoms scattering in the wind (like snow).”

春は雨 外で滑ると どろだらけ

ミア・ピサカーニ Mia Pisacane, Washington Lee High School

地 A wet, muddy day! On the one hand, this poem wonderfully captures the humorous essence of haiku — remember that haiku comes from a tradition called haikai no renga 俳諧の連歌 or “comic linked verse,” in which poets often made amusing puns or humorous observations about the world.

On the other hand, I’m also reminded of the famous opening lines of the 10th-century work Makura no sōshi 枕草子, which begins with this line:

Haru wa akebono 春は曙, “In spring, it is the dawn (that’s the best time).”

Read in this way, the poem becomes a humorous type of “allusive variation” (honka-dori 本歌取り or, in the case of alluding to a prose work, honsetsu 本説). The poet may thus be seen to suggest humorously that the best thing about spring is the rain, since when you slip outside, you get covered in mud!

Of course, as a reader I cannot know whether the poet really intended this, but that is the fun of literary interpretation – and the challenge of hermeneutics (kaishakugaku 解釈学).

春の歌 そよ風が吹く 枝が舞う

マデリン・ワング Madeleine Wang, Lake Braddock Secondary School

人 Excellent use of language here. According to Kokinshu 古今集 (905), an important collection of Japanese poetry (waka 和歌), all creatures in nature possess the rudimentary capacity for poetry or song (uta 歌 — note the word uta really meant “poem” just as much as “song” in classical Japanese). This idea can be traced back to the ancient Chinese classic Shijing 詩経 (Jp. Shikyō, The Classic of Odes), and you have extended it here to cover not just animals but the seasons: the gentle breeze (そよ風) is the “song/poem of spring,” and the branches “dance” in response to its tune. Very nice work!

雲海や 白波立てる 雲の海

メイソン・シュル Mason Shull, Ocean Lakes High School

客 This is a very intriguing poem! The eye is drawn to the repetition of imagery in the first and third ku: at first glance, 雲海 and 雲の海 seem identical in meaning, but are they? The reader wonders why the poet would choose to say the same thing in two different ways, and this becomes a productive line of inquiry. Is it a play on the different nuances carried by Sinitic (kango 漢語) and Japonic (wago 和語) vocabulary? Do the two phrases actually refer to something denotatively different, as opposed to merely having different connotations? Can we construe 雲海 as per its usual meaning — a sea of clouds, perhaps as seen from above, like from an airplane (海の如く一面に広がって見える雲)? Indeed, where is the poet here, and what exactly is he seeing? This kind of excursion is one of the joys of reading poetry, as the ambiguities become multiplicities of meaning, or unresolved mysteries, that enrich the act of reading.

あたたかい わかめのスープ ゆらゆらと

グラジエラ・ソト Graziella Soto, Paint Branch High School

客 A lovely moment of warmth and relaxation! The image of わかめのスープ is especially nice, and ゆらゆら makes me feel as if I’m floating in a sea of warmth and comfort.

星空は きっと夜空の 花畑

デビッド・マーチ David Marche, Columbia Heights Educational Campus

客 This is an excellent foray into the kind of speculative flight that defines the phenomenon of “elegant confusion” — when the poet offers a creative take on something in nature that fuses aesthetic experience and ratiocinative judgment. Here, the poet speculates that a starry sky is in fact a field of blossoms (the stars are themselves the blossoms) blooming in the night sky.

ゆきだるま きらめくつらら こおりみず

アレックス・バンシッキー Alex Van Sickie, Hayfield Secondary School

客 My question here concerns the final ku: usually, the term こおりみず means ice water for drinking (i.e. water in which you’ve intentionally put ice in order to make it cold). Is that the intended sense? Does the icicle provide ice water for you (or the snowman?) to drink?

Regardless, the imagery is good, and the first two ku have a nice euphony (onchō 音調), as the relatively softer, “round” sounds of ゆきだるま contrast with the sharp, “glittering” quality of きらめく, and だるま and つらら are close to being rhymes. Altogether a pleasing poem.

暗い森 しかの鳴き声 葉が落ちる

徐羽・バルズドゥカス Jou Barzdukas, Falls Church High School

客 Some very traditional imagery here: the mournful crying of a stag in the autumn woods was a favorite image of Japanese poets as far back as the 8th century collection Manyōshū 万葉集. Indeed, the imagery in your verse reminds me of the famous Manyōshū poem (also included in Hyakunin isshu 百人一首) in which the stag crying for his mate betells the melancholy of autumn:

okuyama ni 奥山に Deep in the mountains,

momiji fumiwake 紅葉ふみわけ Treading through red fall leaves naku shika no 鳴く鹿の The stag cries;

koe kiku toki zo 声聞く時ぞ When I hear his voice,

aki wa kanashiki 秋は悲しき How sad the autumn seems!

まるい月 星がきらきら 花が飛ぶ

ノーラン・ブー Nolan Vu, Falls Church High School

客 There is a wonderful contrast here, partly conceptual and partly phonetic, between まるい and きらきら: the former feels big, soft, and of course round, while the latter feels focused and sharp. Poets are interested in what we might call the “materiality” of language — how words sound or feel when we enunciate them out loud — and this verse provides some enjoyable euphony (onchō 音調) in the assonance (ruiin 類韻) between hoshi and hana.

J-3. High school Japanese 3 equivalent

木の葉落ち 隠れた命 大地の実

ジアユン・シン Jiayun Xing, Walt Whitman High School

天 Wow, a truly unique conception! Great poems can often be mysterious, their ambiguities offering space for a multitude of meanings to be present simultaneously. I am struck by the implication of a life cycle here, and by the imagistic density of the poem. The second and third ku exemplify a paratactic (heiretsu 並列的) arrangement — two images put side by side, neither one grammatically subordinated to the other (as would be the case in a hypotactic (jūzoku 従属的) arrangement). It is a powerful technique, though easily overused. But it works quite nicely here, since the reader is left to meditate on how “hidden life” and “fruit of the Earth” relate to one another. Excellent work!

あめのうた さくらのダンス はじめけり

アニー・バイ Annie Bai, Oakton High School

地 The song of the rain! As I noted in connection to another poem above, according to the classical waka 和歌 anthology Kokinshu 古今集 (905), all creatures in nature possess the rudimentary capacity for poetry or song (uta 歌) — note the word uta meant “poem” just as much as “song” in classical Japanese. This idea can be traced back to the ancient Chinese classic Shijing 詩経 (Jp. Shikyō, The Classic of Odes), and you have applied it here to a natural phenomenon: even the rain sings a song/poem, and the cherry blossoms dance to its tune.

Also noteworthy is the emphatic auxiliary verb (jodōshi 助動詞) けり, which adds not only emphasis or exclamation (eitan 詠嘆) but also implies a sense of discovery, as if the poet has just noticed the cherry blossoms dancing. Well done!

雪が降る 星が輝く 夜が明ける

アイビー・ダング Ivy Dang, Hayfield Secondary School

人 This verse possesses a strong staccato rhythm and exemplifies the technique of parataxis (heiretsu 並列) — all three ku are simply set in parallel, with no grammatical connections between them. The effect creates quite a different reading experience than, for instance, saying something like this: 雪が降り星も輝 く夜明けかな, which would convey much the same denotative meaning but would not yield the same reading experience. In modern times, parataxis has been used to great effect by poets of the imagist (shashōshugi 写象主義, hyōshōshugi 表象主義, imajizumu イマジズム) school.

蝉が鳴く 風鈴が鳴る 風が吹く

ユービン・ティアン Yubin Tian, Walt Whitman High School

客 This is interesting because it seems to give a kind of life or sentience to the wind chimes: just as the cicada “chirps” (naku 鳴く), the windchimes “ring” (naru 鳴る). The two are set in parallel, implying an underlying similitude between them.

まんげつや はるのそよかぜ はながさく

ウィラーダ・ヒルンキット Wirada Hirunkiji, Hayfield Secondary School

客 Nice imagery in a slightly unconventional mix. In traditional haiku, まんげ つ is a “seasonal word” (kigo 季語) usually associated with autumn, while はな most often represents spring (which is of course the setting for your poem). Of course, full moons happen every month, but such are the traditional poetic conventions. I imagine a lovely spring night, a gentle breeze and blossoms visible in the soft light of the full moon. In modern times, writers of haiku don’t necessarily include kigo in their compositions, or they may play with seasonal conventions in a manner similar to that seen in this verse.

日の笑顔 眩しい天気 熱い愛

デイビッド・トロング David Truong, Falls Church High School

客 A very nice personification (gijinka 擬人化) of the Sun. Also, the choice of the word 愛 is quite apposite here. Japanese has two words that typically translate to “love” in English: ai 愛 and koi 恋, with the latter generally implying romantic love and former being more appropriate to broader, philosophical contexts, e.g., the Mohist concept of “universal love” (ken’ai 兼愛), the equation of “love” 愛 with the Confucian concept of “humanity” (jin 仁), and so forth. In

your poem, the heat and brightness of the Sun is an expression of its love for the life it sustains on Earth.

J-4. High school Japanese 4 equivalent

秋風に 吹かれてわれは 無の中へ

フランシー・下岡 Francy Shimooka, Lake Braddock Secondary School

天 This is a very well-crafted verse that uses a type of enjambment (ku matagari 句跨り) — the われは of the second ku is really the beginning of the third ku — and calls to mind Buddhist contemplation. The term mu 無 is redolent of both Buddhist and Daoist philosophy, and its use in the final ku is nicely consonant with the sense of isolation and solemnity conveyed by 秋風.

春の雨 嬉しくおどる 小鳥かな

クリスティーナ・ド Christina Do, Lake Braddock Secondary School

地 Cute! This is an excellent poem reminiscent of those by the haiku master Kobayashi Issa 小林一茶 (1763-1827), who was known for his poems treating small animals like sparrows (suzume 雀) and ducks (kamo 鴨):

Wayakuya to わやくやと All in a tizzy,

Arare o wabiru 霰を侘びる The sparrows are assailed Suzume kana 雀哉 By a hailstorm

Kyō mo kyō mo けふもけふも Day after day

Damatte kurasu だまつて暮らす He keeps quiet and gets by Kogamo kana 小鴨哉 The little duck

As in these poems, your use of the final emphatic particle かな is also perfect here, as it nicely conveys a sense of discovery at seeing the birds dancing. Well done!

春風に 吹かれておどる さくら道

ヘイガン・恵美理 Emily Hagen, Oakton High School

人 Excellent! Structurally, this is a nice example of what scholar Mark Morris has termed a “linear” poem — one that proceeds straight through like a statement but lacks final predication (i.e., there’s no です or なり or ~をたどる or any other predicate (jutsugo 述語) after さくら道). Many Japanese poems work like this, and your handling of the basic grammatical connections between the ku is very good. Bravo!

落ち葉降る 葉が火の様に 木を燃やす

ウィンストン・スチュアート Winston Stewart, Falls Church High School

客 The image of the leaves – presumably a deep red color – lighting the tree aflame is very effective. One question the reader is left with, however, is which leaves seem like they’re lighting the tree on fire: is it the fallen leaves, or the ones still left on the branches? Or do the leaves look like flames as they fall off the trees? While the image is difficult to resolve with precision, it is creative and very much in keeping with the tradition of keen observation so characteristic of haiku.

J-5. High school Japanese 5 (or higher) equivalent

桜散り 出会いと別れ 告げて行く

森本わかな Wakana Morimoto, Walt Whitman High School

天 Evocative! The juxtaposition of meeting and parting has a very long precedent in Japanese poetry — one thinks here of the very famous waka 和歌 on the Gate of Osaka:

Kore ya kono これやこの This is that place

Yuku mo kaeru mo 行くも帰るも Where those going and coming back Wakarete wa 別れては Part their ways

Shiru mo shiranu mo 知るも知らぬも And friends and strangers meet, Ōsaka no Seki 大阪の関 The Gate of Osaka

In your poem, do the falling blossoms themselves tell of meeting and parting? I’m not exactly sure, but the imagery is perfect!

陽炎へ 徐々に溶けゆく この体

アンドリュー・ホン Andrew Hong, Oakton High School

地 Challenging! This poem again presents an image that is compelling, yet difficult to resolve with precision. That it is hot is plain enough – one imagines the shimmer of hot, summer air radiating off the pavement in July. Is it you who melt into the shimmering heat? And I am struck by the choice of へ in the first ku, as opposed to more conventional particles で (e.g., 暑さで溶ける) or に (e.g. 水に 溶けない物質, “a material that does not dissolve in water”). Still, the verse is effective at conveying a sense of gradual surrender to intense summer heat!

秋になり うでがいたいな 落ち葉かき

マリー・ノーサル Marie Nosal, Hayfield Secondary School

人 This is a very skillful use of a kind of parataxis (heiretsu 並列) in which the logical grammatical relationships between the terms, while not made explicit, is nonetheless perfectly clear. Moreover, the colloquial style of うでがいたいな imparts to the verse a playful quality that dovetails nicely with 落ち葉かき, that most quotidian of autumn chores! Indeed, the second and third ku are extremely skillful.

黒いくま 雪降るガオー 白い熊

ステイシー・ヌエン Stacey Nguyen, Hayfield Secondary School

客 Originally, haiku were often comical poems, as they developed from an earlier tradition called “comic linked verse” (haikai no renga 俳諧の連歌) or just “haikai” 俳諧 for short. As haiku-like poetry became more serious, verses that made overt use of humor or puns came to be called senryū 川柳. These poems don’t require seasonal words (kigo 季語) like traditional haikai (and haiku) did, though yours does contain one. The conception here is creative: a black bear is snowed upon (is it the bear who roars or the snow that roars?), and he becomes a white bear! I imagine him falling asleep, then awaking to find himself covered in snow. Or perhaps he is awake, and roars in annoyance (or happiness?) at the falling snow.

C-2. College 200 level

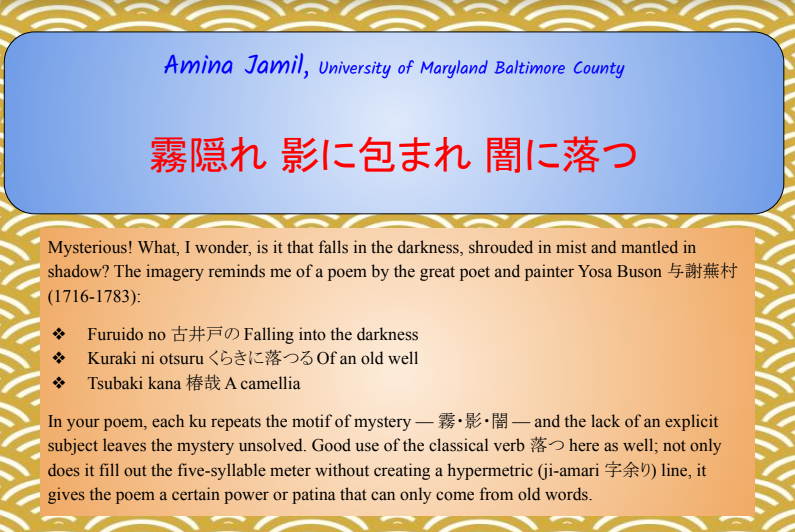

霧隠れ 影に包まれ 闇に落つ

アミナ・ジャミール Amina Jamil, University of Maryland Baltimore County

天 Mysterious! What, I wonder, is it that falls in the darkness, shrouded in mist and mantled in shadow? The imagery reminds me of a poem by the great poet and painter Yosa Buson 与謝蕪村 (1716-1783):

Furuido no 古井戸の Falling into the darkness Kuraki ni otsuru くらきに落つる Of an old well

Tsubaki kana 椿哉 A camellia

In your poem, each ku repeats the motif of mystery — 霧・影・闇 — and the lack of an explicit subject leaves the mystery unsolved. Good use of the classical verb 落つ here as well; not only does it fill out the five-syllable meter without creating a hypermetric (ji-amari 字余り) line, it gives the poem a certain power or patina that can only come from old words.

こううから つくよみのかげ やぶりけり

アッシュトン・ウィル Ashton Will, Randolph-Macon College

地 Intriguing! This verse reminds me a little of a style of waka 和歌 termed “the style of etheral beauty” (yōentei 妖艶体). Associated with the poet Fujiwara no Teika 藤原定家 (1162-1241), the style of ethereal beauty is apparent in verses such as the following:

春の夜の Haru no yo no On a springtime night 夢の浮き橋 Yume no ukihashi The floating bridge of dreams 途絶えして Todae shite Breaks off

峰に分かるる Mine ni wakaruru From the peaks takes leave 横雲の空 Yokogumo no sora A cloud trails slant in the sky

さむしろや Samushiro ya O’er her bed of straw, 待つ夜の秋の Matsu yo no aki no The wind of waiting autumn nights 風ふけて Kaze fukete Grows dark,

月をかたしく Tsuki o katashiku And she spreads the moonlight out: 宇治の橋姫 Uji no Hashihime The Lady of the Uji Bridge

These poems should give a basic sense of Teika’s style of ethereal beauty. In your poem, I am assuming こうう is 降雨. Are you seeing the moonlight “shattered” in a puddle as the rain falls? The use of つくよみ is very nice; beyond helping to fill out the meter, it functions fruitfully as a kind of metonym (or synecdoche) for the moon itself, and it is also the name for a deity of the moon. The idea of the moonlight having been “broken” or “shattered” in the downpour is very reminiscent of Teika’s yōen 妖艶 style, and your use of the auxiliary verb keri is perfect here, as it expresses a sense of discovery or sudden realization. Excellent!

雪中花 弱い朝日に 手を伸ばす

ケート・タトル Kate Tuttle, The George Washington University

人 This poem begins with a very strong Sinitic (kango 漢語) vocabulary word – one that uses very consonant-heavy Sino-Japanese readings (on-yomi 音読み) and takes up all five syllables of the first ku. This creates a powerful opening. The following two ku are gentler, both in their euphony and their imagery, and the resulting contrast is very pleasant. The third ku transforms what was mostly a visual experience into something more tactile.